East Meets West

In the quarter of a century following the Six-Day War, the East German government and the West German far left demonized Israel time and again, often vilely equating it with the worst thing in their own nation’s history: Nazism. Worse than that, they contributed not only rhetorically but materially to the Arab countries’ and the Palestinian terrorists’ war against the Jewish state.

They didn’t do this by themselves, of course, nor did they do it together. East Germany was part of the Soviet bloc, which took its cues on Israel as well as everything else from Moscow; members of the West German far left were closer to their radical counterparts elsewhere in the West and in the Third World than their communist fellow Germans in the East. What they had in common, as Jeffrey Herf demonstrates in his deeply researched new book Undeclared Wars with Israel: East Germany and the West German Far Left 1967–1989, was the perverse and perversely influential depiction of Israel as the true heir to their own people’s genocidal history.

The drab communists who led the German Democratic Republic (GDR) immediately after World War II weren’t anti-Zionist. Indeed, early in 1948 the Central Committee of the East German Communist Party declared: “We consider the foundation of a Jewish state an essential contribution enabling thousands of people who suffered greatly under Hitler’s fascism to build a new life.” But this was merely a reaffirmation of what was, very briefly, the official Soviet line, and when the USSR turned against Israel so did East Germany. By the time that the East German leader Walter Ulbricht visited Cairo in 1965, he could claim that “the issue of Israel was utterly separate from ‘the suffering and injustice inflicted by the criminal Hitler regime on the Jewish citizens of Germany and other European states.’” Israel was, according to him, nothing more than a base of Western imperialism.

Unlike other Soviet bloc nations, East Germany didn’t break relations with Israel after the Six-Day War—because it had never had them in the first place. This was mostly due to its refusal to pay reparations for the crimes of the Nazis. But it did denounce Israel as the aggressor and likened it to the Nazi regime, and “[i]n the weeks following the war, East German officials traveled to Cairo and Damascus to express their solidarity and back up words with agreements to deliver weapons,” often cost-free. In the ensuing years, East Germany’s sales of armaments to the Arab world were relatively small, compared to those of the USSR and some other Warsaw Pact allies, but they nevertheless ran into the hundreds of millions of dollars. The East Germans also supplied the Arab countries with hundreds of military, economic, agricultural, and other sorts of advisers, and admitted large numbers of Arab students into their own institutions of higher education. What motivated them to do this was not simply zeal to comply with the wishes of their Soviet overlords. “Playing the anti-Israel card,” Herf explains, “proved beneficial to the East German regime.” Until then, no country outside of the Warsaw Pact recognized its legitimacy, but in 1969 East Germany succeeded in establishing official diplomatic relations with Iraq, Sudan, Syria, Egypt, and South Yemen.

In the 1970s and 1980s, it was not only the Arab states with which East Germany stood shoulder to shoulder but the increasingly active Palestinian terrorist groups as well, which they supplied with funds as well as (covertly) weapons. There was one quasi-exception to this rule: In 1972, in the aftermath of Black September’s murderous attack on the Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics, the East German government “publicly condemned a terrorist attack whose victims were Israelis.” But even as it did so, it studiously avoided noting whom the victims were or why they had been murdered, condemning only “what it called a ‘crime against the Olympic Games,’ which united the world’s athletes and thereby were ‘contributing to the cause of peace.’”

Until virtually the moment it ceased to exist, the GDR supported Arab terrorist organizations, justified their actions against Israel, no matter how vicious, and even offered their members safe haven. In the eyes of its official newspaper, Neues Deutschland, it wasn’t, for instance, the PLO that was responsible for the massacre of Israeli schoolchildren in Ma’alot in 1974; it was “Tel Aviv’s breaking of its word” to the hostage-takers that led “to the deaths of children and Palestinian partisans.” Where the East Germans drew the line, however, was at providing a base of operations for groups that planned and implemented attacks on Jews and others on Western European soil. As Herf explains, this was because they feared that it would “undermine support for détente in Western Europe and for continued West German financial payments to East Germany.” Consequently, the East Germans drew a convenient distinction between the “moderates” it supported and the “extremists” it did not:

An “extremist” was a terrorist who extended “the international class struggle” to include attacks in Western Europe while a “moderate” was a terrorist from the Arab states or the Palestinian organizations who focused attacks only against Israel, and perhaps “imperialist” targets outside Western Europe.

This wasn’t their only hypocrisy. While the East German government endorsed the Palestinian right of return, it vigorously opposed the prospect of the millions of Germans who had been expelled from Eastern European countries in the aftermath of World War II returning to their homes as a revanchist “threat to peace and stability in Europe.”

The West German far left emerged in a society that believed its own legitimacy to be bound up with a Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms with the past) that entailed not only repudiation of the Nazis but reparations to their Jewish victims. While East Germany was denying any responsibility for the Nazi regime and excoriating Israel, West Germany was transferring massive amounts of money to it and offering the country its broad support. In line with the rest of the country, “the preeminent stance of non-communist leftist and left-liberal opinion in West Germany was emphatically pro-Israeli” in the years between 1949 and 1967. But Israel’s trouncing of its enemies in the Six-Day War gave pause, at least, to leftists throughout the world, and those in West Germany were no exception.

Herf shows that something close to happenstance also had a role in the German New Left’s turn against Israel in 1967. On June 2, three days before the war began, a policeman named Karl-Heinz Kurras shot and killed a Berlin university student, Benno Ohnesorg, who was protesting the visit of the shah of Iran. This sparked unrest that culminated on June 10 in a 7,000-student-strong protest march in Hannover, Ohnesorg’s hometown, on the day of his funeral. In the days following this event, the conservative German press, controlled by Axel Springer, simultaneously vilified the New Left and extolled Israel’s historic victory; the friend of the leftists’ enemy became their enemy. “For the young Left,” Herf writes, “the conjuncture of the Six-Day War and the Ohnesorg shooting had enduring import.”

Within three months, the Socialist German Student League (SDS) denounced Zionist colonization and immigration, called for the return of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees, and condemned “the Israeli aggression against the

anti-imperialist forces in the Middle East.” The SDS’s adoption of this resolution was, Herf writes, “the moment at which the leftist anti-imperialism of the 1960s New Left . . . redefined the meaning of West German Vergangenheitsbewältigung and its associated focus on the memory of the Holocaust and . . . anti-Semitism.”

Over the next several years, SDS members began showing up at “Al Fatah summer camps” in Jordan, sometimes receiving military training. In 1969, Dieter Kunzelmann, a key leader of the West German far left, summed things up in a “Letter from Amman”:

Palestine is what Vietnam is for the Amis [slang for Americans]. The left has not yet understood that. Why? [Because of] the Jewish complex (Judenknax). “We gassed 6 million Jews. The Jews today are called Israelis. Whoever fights fascism is for Israel.” It’s as simple as that but that’s all wrong. When we finally learn to understand the fascist ideology of Zionism, we will no longer hesitate to replace our simple philo-semitism with an unambiguous and clear solidarity with AL FATAH. In the Middle East, it has taken up the battle against the Third Reich.

For the most extreme of the West German far leftists, solidarity with terrorists predictably extended to collaboration with them. Herf sketches the short careers of the most notorious of these people, Wilfried Ernst Böse and Brigitte Kuhlmann, who collaborated with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in hijacking an Air France flight and diverting it to Uganda, where they were killed by Israeli commandos during Operation Entebbe. He also tells us about their comrades in the Revolutionary Cells who bombed many Jewish and Israeli sites in Germany between 1973 and 1980. Among these attacks were several attempted bombings of European theaters screening Victory at Entebbe, a 1976 extravaganza that starred, among many others, Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster, Elizabeth Taylor, Linda Blair, Theodore Bikel, and perhaps most improbably, Richard Dreyfuss as the heroic Lieutenant Colonel Yonatan Netanyahu, who was killed while commanding the operation.

In his 1979 Return to Humanity: The Appeal of a Terrorist Who Has Abandoned Terrorism, Hans-Joachim Klein renounced his Revolutionary Cells past and expressed pride in his part in thwarting the assassination of two West German Jewish leaders. Nearly two decades later, however, when the remaining members of the Red Army Faction dissolved their organization, the only other group “that they praised by name” was the PFLP.

The stodgy East German leaders didn’t learn any lessons from the West German firebrands, and one can’t say anything more of the latter group’s anti-Zionist statements from the Six-Day War onward (and Herf says it a number of times) than that they echoed what the former had long been saying.

There is, however, the curious fact that the West German policeman who shot Benno Ohnesorg was secretly a Stasi agent. “Ironically,” Herf observes, “a murder carried out by an agent of the East German intelligence services became conclusive evidence for West German leftists that the West German government and the Social Democratic government of West Berlin as well were intolerant of dissent.” But even if this policeman had intended (as he subsequently denied) to stir up trouble, it couldn’t have been with the aim of ruining the relations between the West German left and Israel.

In 1990, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the first (and only) freely elected East German parliament voted in near unanimity to ask “the people in Israel for forgiveness for the hypocrisy and hostility” of the country’s previous policies toward their state as one of its first acts. Not long afterward, it adopted another resolution renouncing “all forms of the anti-Israeli and anti-Zionist policies that were practiced in this country for decades . . .” Every party in the parliament supported this resolution, except the Communist Party’s successor.

Jeffrey Herf has produced not only a prodigiously researched indictment but also a timely reminder. As he writes at the very end of his book, although they have been defeated, the communists and radical leftists in Germany

left behind a toxic ideological brew. Their distortions about the history of the state of Israel, their extensive use of terrorism, and their justifications for it have cast a long and destructive shadow over politics and political culture in the Middle East, in Germany, and around the world.

Undeclared Wars with Israel is, then, a post-mortem with a polemical edge, a book that very carefully digs up half-forgotten enemies of Israel from the recent past, in part to remind us that they have heirs who still repeat the same arguments, slogans, and calumnies. It is, unfortunately, doubtful that Herf’s tale of two hatreds would shame them, even if they read it.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Vegetarian in Vilna

The long, brutal winters and meaty cuisine of Eastern Europe don’t immediately make one think of garden-fresh vegetarian recipes.

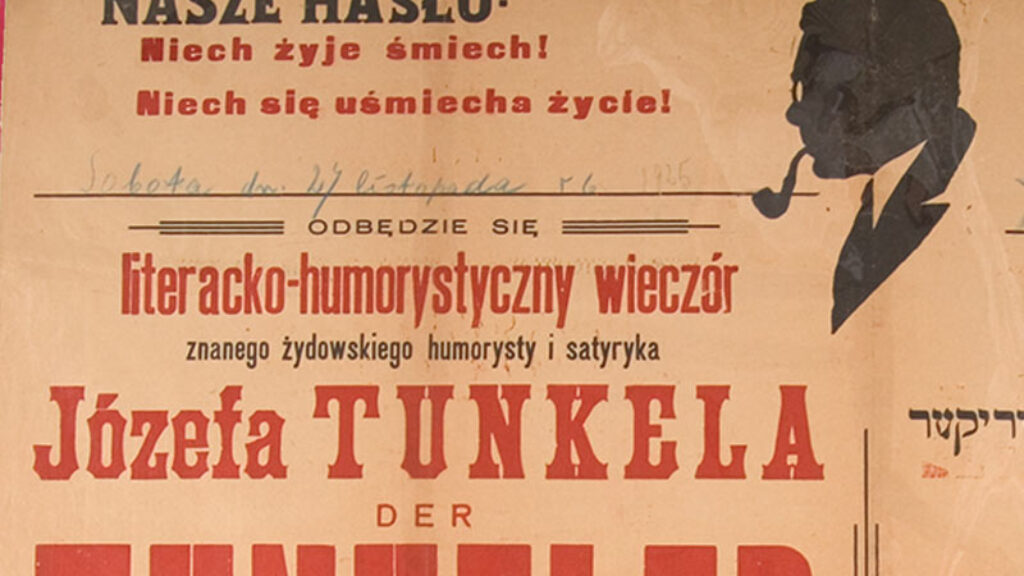

Spinoza in Warsaw: Fragments of a Dream

“Having rested in his grave for 250 years, Baruch Spinoza came to the conclusion that just lying around like that was without telos” and decided to try to make it in Warsaw. A Yiddish satire, translated and with an introduction by Allan Nadler.

Lost in Translation: Song of Songs and Passover

Why is this Targum different from all other Targums?

When Eve Ate the Etrog: A Passage from Tsena-Urena

There was once a custom for a pregnant woman to bite off the tip of the etrog at the end of Sukkot. This excerpt includes the text of a Yiddish prayer, or tkhine, that the pregnant woman is instructed to recite based on an interpretation of Genesis 3:6.

gwhepner

COMING TO TERMS WITH THE PAST

The Germans, not the Greeks, have got a word for it

Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which means

the past should not be something that you choose to spit

out or at, but something that has liens

upon the future that you must accommodate,

while making sure that it is understood,

including complicated parts you must relate

although you can’t relate to them. The good

is oft interred with bones, they say Mark Anthony declared,

but we decide that what’s really rotten

like dirty laundry should be regularly aired

and never be, like what is good, forgotten.

And yet we have to come to terms with what has passed,

not feel eternally condemned by deeds

committed in the past, though we are aghast

at ancient crimes as well as ancient creeds.

Those crimes and creeds can’t be rewritten but they can,

by being understood, enable us

to realize that every action that we plan

is one that our descendants will discuss.

[email protected]